Use Of “ba” – An Elementary Lesson

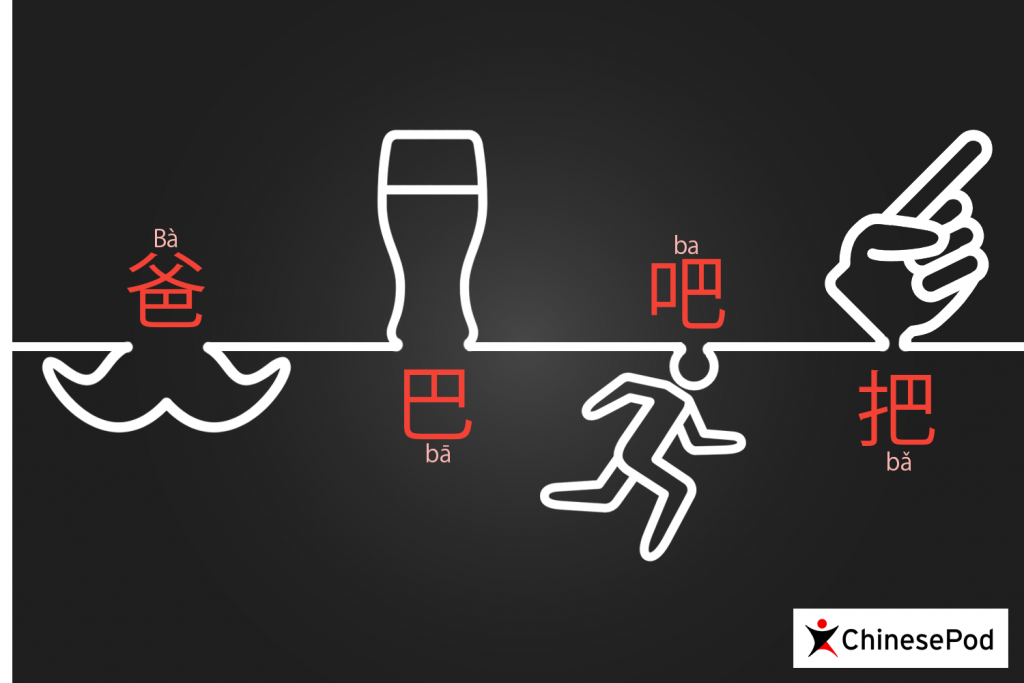

Learning Chinese is a magical journey made accessible and satisfying by recognizing new patterns. Here are four common Chinese characters based on 巴, all delightfully discussed and explained. 巴, 把, 爸, and 吧, are often used and very useful characters to master. They all use ‘ba’ as a phonetic sound but differ quite dramatically in tone and how we use them.

Learning how to properly use the different ‘ba’ sound commonly heard in Mandarin will make learning Chinese just that little bit easier. Here’s a quick look to contextualize what you can take from this article:

- Tone: One of the most difficult parts about learning Chinese is getting used to the tones. For native speakers or speakers of tonal languages, this tends to be a lot easier. A Vietnamese student may learn basic Mandarin quite comfortably in no time at all just by hanging around the market and chatting to locals. If you didn’t grow up with a tonal language, it’ll take your mind a while to get used to using tones as a diction marker.

- Common sounds: When listening to Chinese as a newbie, there are a couple of sounds you’ll hear often. One of them is ‘ma’ and another is ‘ba’. Knowing the typical characters responsible for these sounds is very handy. For this article, we’ll be looking at the ‘ba’ sounds and hopefully be taking some of the mystery out of it.

- Common radical: 巴 (bā), 把 (bǎ), 爸 (Bà), and 吧 (ba) are useful because not only are their tones different, but their grammatical use is so different that you can’t mistake one for the other (once you have some idea what they’re used for…). These have been picked for this because they all share the ‘ba’ sound and the 巴 Chinese character, which makes it useful for practice and memory.

- Using tones: You’ll notice that there isn’t a second tone (ba) character included. That’s because there isn’t a common enough character that fits into the explanation above. Having something using the second tone would have tied the room together nicely, but if you’re looking for a short phrase to help you remember the first four Mandarin tones in general, try 酸 甜 苦 辣 (Suān tián kǔ là). It literally means ‘sour, sweet, bitter, spicy’, and refers to the ups and downs of life, kind of like ‘valleys and hills’ or ‘to take the good with the bad’.

- Crux grammar: 把 (Bǎ) is instrumental in learning Chinese since it marks an important grammatical structure that needs to be mastered if you’re to move on in your studies. If the others seem simple enough after skimming through, make sure to spend some time with 把 (Bǎ)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=i4YJSUOBzP8&t=36s

Chinese for Daddy: 爸爸 (Bàba)

Let’s start with the easiest and least ambiguous of these ‘ba’ characters, namely 爸 (bà). Simply, it means “dad”. It’s often used as 爸爸, which unsurprisingly means ‘daddy’. It’s pretty cool to think about 爸爸 and its sound since it mirrors what children call their daddies in many other languages. In Hebrew, for instance, it’s ‘abba’, in Zulu it’s ‘baba’, and in German, ‘papa’. It’s not far from ‘dada’ in baby talk, and there is only one other term that seems to hold this well universally: ‘mama’ Here’s some more about 爸爸:

- Chinese celebrate Fathers’ Day on August 8th. This is because the date is 八月八日(Bā yuè bā rì – 8 month, 8 days), and can be said as 八八 and thus shares the ‘baba’ sound with ‘daddy’. You may have noticed that the tones are different, but let’s not get too distracted.

- The 爸 character is made up of two parts. At the bottom, you will see the 巴 part, which from the introduction we know gives us a good clue about the ‘ba’ sound. On top of that is a 父 (Fù) part. This character means ‘father’, a more formal term than ‘daddy’. 父 is often seen in 父母親 (Fùmǔ qīn – parents), or 父親 (Fùqīn – father).

- When using it in a sentence, the possessive 的 (de) typically falls away. For instance, you’d say 我爸爸愛吃肉 (Wǒ bàba ài chī ròu – my dad loves to eat meat), instead of 我的 because that possessive 的 (de) falls away when talking about your close family. The same goes for talking in the second and third person, so your dad and his/her dad also loses the possessive 的 (de) – 你/妳爸爸愛吃肉 (Nǎi bàba ài chī ròu – Your dad), and 他/她爸爸愛吃肉 ( Tā bàba ài chī ròu – His/Her dad ).

Chinese for Bar and clinging to your barstool 巴 (bā) & 酒吧 (Jiǔbā)

We’ve already noticed how the 巴 (bā) radical/character appears in all four of the characters dealt with in this article and how they’re all pronounced ‘ba’. Knowing this character and its sound is more useful than knowing what it actually means at lower levels.

- Often, 巴 (bā) is used for its sound in transliteration, like ‘Obama’ – 奧巴馬 (Àobāmǎ), ‘Brazil’ – 巴西 (bāxī), or ‘Paris’ – 巴黎 (bālí).

- After a long day of studying Mandarin, you might get thirsty and decide to look for a ‘bar’ – 酒巴 (Jiǔbā – booze/alcohol bar [transliteration]). Often you’ll also see ‘bar’ written as 酒吧, but despite the addition of the 口 radical, the pronunciation stays the same, first tone ‘ba’.

- Ultimately the character 巴 actually refers to some form of ‘to cling to’. For instance, 飯巴了鍋了 (Fàn bāle guōle – The rice has stuck to the pot), or 巴鍋 (bāguō – crust). It’s often used in conjunction with hope (望 – wàng) to mean ‘to hope earnestly’ or ‘to wait anxiously’ in 巴望 (bāwàng). You can remember it as ‘clinging to hope’, as a useful way to help remember the meaning of 巴.

Chinese for let’s (well, sort of) 吧 (ba)

吧 is mostly used as a particle at the end of a sentence to mean something like ‘let’s’. Similar to ‘let’s’, it could point to a suggestion or a request. Sometimes it could also be a softer command, like ‘Let’s not press the red button lest you want to start the next world war’

- An easy and often heard example is 我們走吧 (Wǒmen zǒu ba – ‘Let’s go’, literally – ‘We walk let’s’). You might hear native speakers use the word ‘okay’ when speaking, but by itself, it refers to something like a condition of affairs being alright – 這個還 OK (Zhège há OK – That’s still alright). If you’re answering a suggestion such as, ‘Let’s go to Borneo this summer’ you could reply 好吧 (hǎoba – Agreed, let’s do it; simply: Let’s) or the colloquial ‘OK 吧’, which means the same.

- 吧 is also used in rhetorical questions. If you asked your dog 你喜歡吃鞋子嗎? (Nǐ xǐhuān chī xiézi ma? – Do you like eating shoes?) we may think you’re expecting an answer. Change the 嗎 (ma) for 吧 (ba) and we know you haven’t lost it yet – 你喜歡吃鞋子吧? (Nǐ xǐhuān chī xiézi ba? – rhetorically; Do you like eating shoes?)

- Like a lot of characters with 口(kǒu) as a radical, its specific usage will keep you busy for a long time. Lots of these words are used at the beginning or end of a statement as a subtle adjuster of the whole sentence’s meaning, and mastering them will prove a longer term challenge.

Chinese Clarification (or emphasized ‘pointing’) – 把 (bǎ)

The last ‘ba’ we’re looking at is super useful, but it’s difficult to find an English equivalent. An easy way to think about 把 is as a clarification tool.

- Imagine you have a misunderstanding: your dad tells you to wash up – 你洗了一點吧 (Nǐ xǐle yīdiǎn ba – How about you wash up a little?). You say you’ll go take a shower and dad tells you that you misunderstood: 你以為錯了! (Nǐ yǐwéi cuòle! – you understood wrong!) 我是説 (Wǒ shì shuō – what I said was:) 你把盤碗洗了一點吧! (Nǐ bǎ pán wǎn xǐle yīdiǎn ba! – You should do the dishes!).

- Another way to think about 把 is to think about it like the phrase ‘to take’ added for emphasis. ‘Take the car and wash it’, or ‘take the salt and give it here’. In this way, it’s handy for giving instructions, like when cooking a dish and you’ve got all the ingredients in front of you. “Now, take the bowl of flour and pour it into the mix.”

- What 把 does is to point out the object or person to which/whom the action should be taken on. It always follows this basic form: 把 + object + verb. In English it would be like giving object oriented instructions in this order: “The red button; don’t press it”. It doesn’t need a subject, but if you use one it goes before 把: “You. Red button. Don’t press.”, or 你把紅紐不要按 (Nǐ bǎ hóng niǔ bùyào àn). To use the cooking example from the previous paragraph with an added subject: “Now you take the bowl of flour and pour it into the mix.”

- A great little source about clarifying a misunderstanding using 把 can be found a previous article. After an ankle injury because of a fall, the speaker goes to the doctor. The doctor asks where else they fell and the guy says on his backside. The doctor says 來, 拉下來一點, 我看看 (Lái, lā xiàlái yīdiǎn, wǒ kàn kàn – Come, pull it down a little, let me have a look). The guy quickly says that there’s nothing wrong with his backside, so the doctor clarifies 我是說把襪子拉下來, 我看腳踝 (Wǒ shì shuō bǎ zǐ zǐ lā xiàlái, wǒ kàn jiǎohuái – I said/meant take your sock(s) and pull it down, I want to look at your ankle. Relieved, the fellow replies: 我以為叫我把褲子拉下來呢 (Wǒ yǐwéi jiào wǒ bǎ kùzi lā xiàlái ne – I thought/understood [you] told me to take my pants and pull them down!)

- Here’s a lesson about moving objects around also using the 把 as a clarifier of which object is being referred to.

Having the knowledge about these different uses of the‚ “ba” sound when learning Chinese is a very useful step. The next and more important part is to find ways to practice it in all of your Chinese disciplines to ensure it becomes a skill. Skill is ultimately what will build competence and, ultimately, mastery of Chinese.

To continue learning about other grammatic rules, check out our play list:

Afrochina

Latest posts by Afrochina (see all)

- Use Of “ba” – An Elementary Lesson - August 9, 2017