Tone Change Rules for Common Chinese Words

In my previous post I talked about my first Thanksgiving dinner in China. Not only did I talk about my dining experience, but I also referred to some Chinese words that I learned along the way, such as ham( 火腿 huǒtuǐ), turkey(火鸡 huǒ jī), pizza (比萨 bǐsà), et cetera. Within the parenthesis I provide to you the Chinese character of each word, and next to each character I provide to you the pinyin. The pinyin is the way in which foreigners learn to pronounce Chinese words, and without it, learning Chinese would be much more difficult.

Source: https://commons.wikimedia.org/

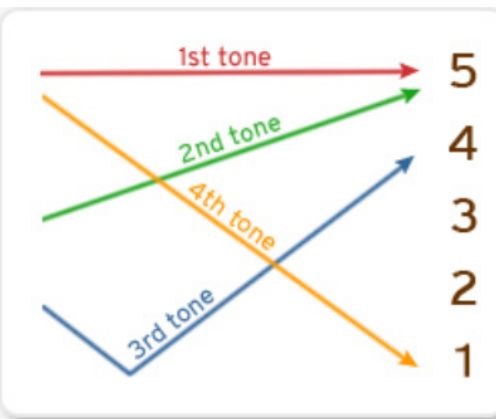

Do you notice the squiggly lines you see on top of each pinyin? They are the tone-markers to help you sound out the pinyin in the right tone! As Chinese learners, I think we can all agree that tones can be quite confusing and difficult to grasp. In addition to learning the tones, we also have to learn the tone rules. Tone rules are the rules that each tone follows when preceding or succeeding another tone.

In the beginning the tone rules might sound confusing, but with some practice you will be able to grasp it in no time. In the former paragraph I wrote the word ham (火腿 huǒtuǐ). It’s clear that the word ham has two third tones (huǒtuǐ), but when two third tones are placed together, the first word, or in this case (huǒ) will become a second tone or a rising tone and the second word (tuǐ) stays the same. Even though it will be written the same (火腿 huǒtuǐ), when saying (huǒ) you will have to say it in the second tone.

A similar pattern occurs a lot with the word bù. Even though bù is a fourth tone word, when preceding another fourth tone word, it becomes a second tone or a rising tone. A few examples are 不会(bù huì) which means unable to/will not/do not know to; 不用 (bùyòng) which means no need, and 不要( bùyào) which means not to want to/no need to. The correct way to pronounce these words is by changing 不 (bù) into a rising tone or a second tone. At first it might seem a bit complicated, but with practice these tone changes becomes second nature.

Another word that changes its tone very often is the word 一 (yī). When 一 (yī) is followed by a fourth tone, it becomes a rising tone or second tone. Here are some examples how 一 (yī) changes its tones: 一个 (yīgè)should be pronounced with 一 (yī) acting as a second tone or a rising tone. Next, we have 一样 (yīyàng), the yī should be a rising tone.

At first the tone rules might seem confusing, but I promise you with enough practice, they will become second nature. It is very important to not feel overwhelmed by the tone rules, doing so will hinder your cognitive abilities. Approach the tone rules with an empty mind, in a playful manner, and you will notice that you will be able to understand them better and quicker. I hope this blog post helped some of you clarify some tone rules and give you more confidence when speaking Chinese. I hope everybody had a great Thanksgiving, and happy holidays to come!!

ChinesePod

Latest posts by ChinesePod (see all)

- Tone Change Rules for Common Chinese Words - December 12, 2019

- ChinesePod’s Founding Story - October 10, 2019